OBJECTIFICATION AND WOMEN EMPOWERMENT: The social media scene – Blog Post

To objectify someone means to make use of them or their image for purposes that do not dignify them as human beings. The most frequent form of objectification of women is sexual objectification, when women are turned into aesthetic/sexual objects at the disposal of others.

In a society where media is the most persuasive force shaping cultural norms, the collective message we receive is that a woman’s value and power lies in her youth, beauty, and sexuality, and not in her capacity, inner-self or passions. The objectification and sexualization of girls and women in the media have contributed to harmful gender stereotypes worldwide.

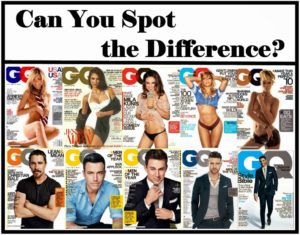

Most of the time, the objectification of women’s bodies is produced on the basis of an isolation or emphasis given to a specific area of the body, such as the mouth or breasts and other “erotic areas”, to the detriment of others. This eroticism is not only produced by nudity, but also arises from the context, objects, the gesture or posture of the subject, the dress or accessories, the way they are worn, and even the way the body itself is shown or hidden. Media advertisements have been used to influence this perspective of the standards of how women should look and portray oneself to the mass audience. It has also been seen that women in the media have been increasingly objectified over the years, thus making women subjects of sexual objectification.

But female objectification is no longer relegated to magazines and TV. Social media delivers the message straight to our phones, establishing a direct line of communication with influencers and cultural figures who teach that objectification is empowerment, that hypersexuality is liberation, and this is constantly reinforced. This hyper-sexualisation has been shown as a form of women’s liberation. But is this really like this when the value of women lies mainly in their sexual potential and in others recognizing it through “likes” in applications such as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook or Tik Tok?

Of course, arguing that women shouldn’t be objectified doesn’t mean that women should be ashamed of their bodies or their sexuality! There’s a difference between sexualization and a free self-expression of our sexuality. Of course, wearing sexy clothes, cleavage, high heels or showing off our bodies does not automatically make us an object. Being proud of our bodies and our sexuality does not make us better or worse than anyone else. The idea that the way a person dresses is the reason why he or she can be assaulted is aberrant since the dignity of an individual cannot depend on the way he or she dresses. The problem is when the body itself becomes the priority value over the attributes of a complete and complex person, or when we need to reinforce our self-esteem through how others value our body. This is harmful considering that beauty cannons are so stigmatizing.

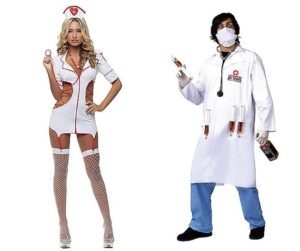

Let’s start talking about costumes now that Halloween is coming and some people like to dress up. If we Google “Halloween costumes” we will see that the erotic and seductive is an exclusive patrimony of the feminine. A man’s costume has to be scary or funny, a woman’s costume has to look good on her. Her body has a plus as an instrument, a toll for which men do not have to pay.  This sexy aesthetic inherited from a sexist and unequal society enslaves women and the worst thing is that it goes unnoticed in the eyes of women themselves. The problem is to identify the sensual and erotic with a single gender. The men’s costume has to be funny, it doesn’t have to be sexy. Not so the vampire girl, this one has to be desirable. Girls have to be sexy or at least cute. Does this really empowers us? Of course I can disguise as sexy nurse or vampire if I want, but it can become a weapon when a girl’s popularity is based on her sexual desirability.

This sexy aesthetic inherited from a sexist and unequal society enslaves women and the worst thing is that it goes unnoticed in the eyes of women themselves. The problem is to identify the sensual and erotic with a single gender. The men’s costume has to be funny, it doesn’t have to be sexy. Not so the vampire girl, this one has to be desirable. Girls have to be sexy or at least cute. Does this really empowers us? Of course I can disguise as sexy nurse or vampire if I want, but it can become a weapon when a girl’s popularity is based on her sexual desirability.

This internalized sexual objectification has been linked to problems with mental health. Hypersexualized models of “femininity” in the media not only contributed to harmful gender stereotypes but also to the mental, emotional and physical health of women on a global scale. Consequences of hyper-sexualization for girls and women include anxiety about appearance, feelings of shame, eating disorders, lower self-esteem, etc. Definitely, hyper-sexualization turns our body into a battlefield! We have been told that a girl’s success is in being desirable without being aware of what this means, when actually, it is nothing more than a pseudo empowerment that neither frees us, much less empowers us. On the contrary, it merely perpetuates the same old roles.

It is no surprise that so many girls participate in this dynamic. In a patriarchal society, girls and women who most assimilate the precepts of patriarchy are given a prize, in some cases, even a crown! Beauty pageants, for example, are a celebration where beauty (a stereotyped kind of beauty) in women is criticised and debated, sometimes presented as a celebration of women’s pseudo-empowerment. Like all systems of oppression, beauty pageants seek to modernise not because they are acquiring new social sensitivity, but just to perpetuate themselves and give the impression that they are keeping up with the times.  A patriarchal system not only imposes stereotypes of beauty and behaviour on us, but conditions us to internalise the message that it is really us who want those standards. When we socialise women to crave a beauty crown, we socialise them to repeat to themselves “Pick me. Declare that I am the prettiest in the Universe. Tell all the others that they are not as beautiful as me. Validate me as a woman.” Let’s be honest, empowerment that comes only with a crown, and for only certain women, is never empowerment but oppression in a different outfit.

A patriarchal system not only imposes stereotypes of beauty and behaviour on us, but conditions us to internalise the message that it is really us who want those standards. When we socialise women to crave a beauty crown, we socialise them to repeat to themselves “Pick me. Declare that I am the prettiest in the Universe. Tell all the others that they are not as beautiful as me. Validate me as a woman.” Let’s be honest, empowerment that comes only with a crown, and for only certain women, is never empowerment but oppression in a different outfit.

We become encouraged to upload sexy selfies, pictures of our achievements, or whatever makes us appear attractive or successful to receive more “likes” and followers from others. Though we believe we have complete freedom in choosing what we post, ultimately the approval from others drives our motivations to post content catered towards their needs. Not necessarily our own.

In this sense, research like Amber L. Horan’s work Picture This! Objectification Versus Empowerment in Women’s Photos on Social Media (Bridgewater State University) supports the hypothesis that the number of “likes” a photo received is correlated with sexualization of Instagram. This partially confirmed Simone de Beauvoir’s concept of self-objectification, where young women generally see themselves as objects for viewers to judge through “likes”.

Let’s now think about “Only Fans” platform; many women have decided to join it and defend its use under the argument that “it is their body, and they decide what to do with it”, thus mentioning the so famous female empowerment, but is there really a free and conscious decision of what women can do with their bodies?

This “progressive” idea of empowerment allows us to break away from all these conservative rules, continuing to replicate them now with “freedom”, with “our consent” and with a lot of men “allied” who continue to look at us again as an object, without changing anything. Many types of industries such as porn, music, film and video games have reinforced and created an ideal of woman that we should all aspire to, an ideal that is moulded 100% to male comfort and pleasure and this ideal is sold to us so that we women feel even empowered to achieve it. The consequences of online objectification could be devastating, and the scary thing is that it is happening without us really knowing it. How can we feel free, how can we say “it’s my decision” in a society that constantly imposes new gender stereotypes? In which way can we make a conscious and free decision within all this socialisation we grew up with?

In this social context, it makes no sense to think that female sexualisation is an expression of female competitiveness and empowerment. In what sense ‘sexy selfies’ are a step forward to gender equality and/or women emancipation? It’s so simplistic to argue that the women who self-objectify themselves are not a victim but a kind of strategic winner in a complex social and evolutionary game.

The social rewards that society gives to women for objectifying themselves conforming to socially established patterns is perpetuating female subordination, increasing “benevolent sexism” and weakening a real women’s collective action against patriarchy. Although some may dream of a post-gender world, we are not unfortunately there. Late capitalism views women as having a privileged set of marketable attributes that are primarily connected to their reproductive functions. Objectification acts to shape women as both consumers with buying power and as consumable objects. The hegemonic order is still racist, classist and sexist, and it is finding new and creative pathways in which to discriminate. Hyper-sexualization is one of it.

Some ideas to fight against these stereotypes:

- Promoting a critical youth media literacy to develop the ability to reject hypersexualized models of femineity we’re being sold.

- Fight toxic masculinity, gender roles and objectification in your daily life (small actions always add up)

- Teach girls that their worth isn’t defined by their looks or bodies.

- Share media that portrays powerful women without their physical appearance and sexuality playing a main role in their self-esteem.

- Teach sexual education to children and make it a safe and useful space for them to identify and speak about their experiences.

- Show more diverse and realistic portrayals of girls and women in the media.

- Remind yourself and your beloved ones that your value is in yourself, not in the approval of others.

Post by Sonia Suarez (Training Specialist

of Engage Nepal with Science)